EMPEREUR CHARLES V 1500/1558 Héritier des Habsbourg et de la maison de Bourgogne, Héritier de 17 couronnes

BEING BLACK, MELANIN THIS DIVINE BLESSING

www.la-melanine-une-benediction.com

SITE UNDER RENOVATION

info@la-melanine-une-benediction.com In Englishwww.melanin-a-blessing.com

ATTENTIONWE ARE ATTEMPTING TO BLOCK THIS SITE BY CALLING IT DANGEROUS. DISREGARD ANY WARNINGS, THIS SITE IS SAFE AND WELL PROTECTED with Kaspersky (the most reputable anti-virus). They do everything to prevent us from having access to our knowledge.STRONGLY RECOMMEND THIS SITE TO YOUR FRIENDS

The purpose of this site is to bring black people to self-awareness, to realize that with Africa cradle of humanity,(Africa)they are at the origin of all inventions: inventions -in all fields ofknowledge, as far back as one can trace- monopolized, copied and improved by the leucodermas who usurped them and declared themselves their inventors. Since High Antiquity, blacks have been the inventors of culture: arts, sciences, maths, philosophy, music, religion, engineering, medicine, surgery, astronomy, navigation etc... before whites stripped them of them and falsified them at their advantage. All science is related to Egypt which was a country populated by blacks.It is thanks to this black pigment present in abundance in their brain: neuromelanin,that black had and has this high capacity for creation, invention at all levels.

This site reveals the horrors and monstrosities put in place by the whites in order to degrade and reduce the blacks to the lowest level to justify their stripping, because the deficiency of the whites in this neuromelanin pigment did not allow them to equal the blacks. But neverthelessfor blacks, the purpose of this site is to be informed about them and their opponents: whites in order to be able get up and react, feel proud of themselves, grateful for their neuromelaninand their melanin, no longer allowing themselves to be reduced, degrading but having a win-win relationship in their relations with white people, no longer having this win-lose relationship which has always prevailed and continues to prevail ; the eternal winning the white, the eternal losing the black.Fueling resentment and anger towards them puts us in a losing position and has harmful effects on our health. We blacks must be diplomatic and lucidly seek our true interests in win-win relationships with leucodermas without bringing out resentment.

Isn't knowledge of one's past, of one's culture the first forms of resistance to exploitation and oppression?

Watch out, the wheel is turning, the West is in decline, the world is heading towards multipolarity. I'Africacontinent holding all the wealth of the planet, continent that does not know natural disasters,has its major role to play.Besides that our economic relations must be win-win with all our partners including Russia, China; before signing any partnership with any Western country (especially France), we must demand from them a written and signed commitment to reparations for all crimes (blood, looting, etc.) committed against us , because they have the blood of millions of Africans on their hands. We must also set up our own International Criminal Court to try all those Western criminals who abused us without mercy.We will be globally respected the day we command and inspire respect.

Dear visitors,see for yourself! : my videos are often deactivated, although very active on you tube, my visit counter had been removed (I put it back), as well as certain images. Would revealed truths bother?Recommend this site to those around you

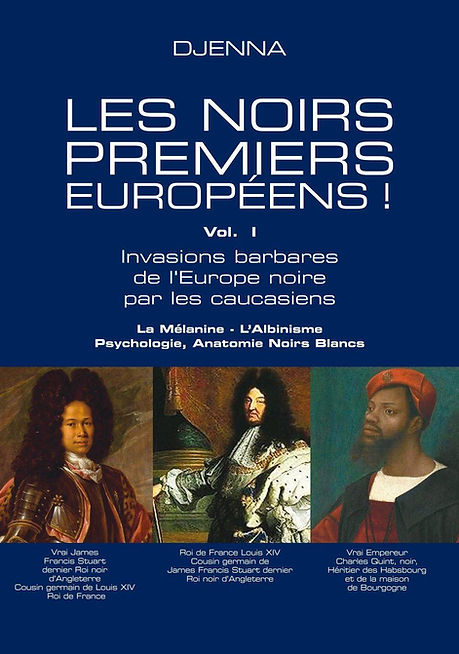

Read the book ''Les Noirs 1ers Européens''

Sold by theTamery bookstorein Paris. General Library Guadeloupe The true history of blacks in Europe. 5th edition

" The manipulation of the past is an instrument of power: the winner to legitimize his conquests, the oppressor to justify his violence alter, disguise the past of their victims. Source: B Saint-Sernin: Political Action according to SimobornWeil pp53

-There are two Histories: the official, lying history that is taught; then the secret history, where are the true causes of the events: a shameful history "(Honoré de Balzac, writer)

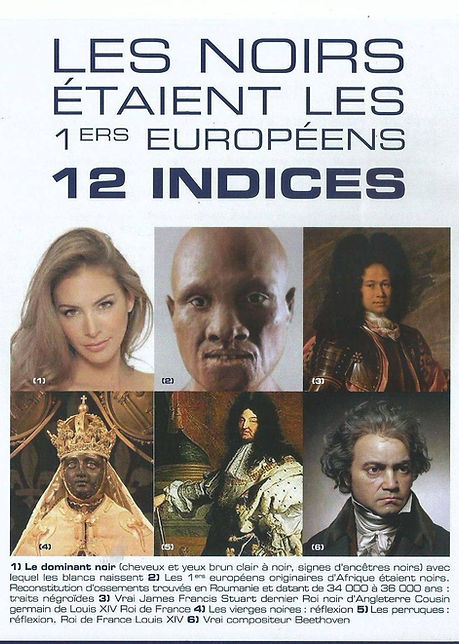

We Blacks MUST KNOW that we have been victims since the 18th century by the leucodermas (the whites) of the most vast and monstrous impersonation of our kings, queens and famous people of Europe, that history has ever known. We are also victims of the greatest and diabolical falsification of history ever carried out. The leucodermas have done this diabolical work of make-up and crime with the help of their globally present secret societies.

Isn't knowledge of one's past, of one's culture the first forms of resistance to exploitation and oppression?

SLAVERY AND SLAVERY

slave ship

THE CAUSES OF THE SLAVE TRADE AND COLONIA SLAVERYI(CM98.FR)

The Atlantic slave trade began in the 15th century when the Portuguese began to buy men from the coasts of Africa which they were then exploring.

slave Europe

Most European nations participated in the Atlantic slave trade and contributed to colonial slavery:

– either by organizing slave expeditions,

– either by financing expeditions (such as Switzerland for example),

– or by producing goods for trade on the African coast and for the purchase of captives or the operation of plantations.

A few countries were particularly active in organizing slave expeditions:

Country et Slave expeditions

England 41%

Portuguese 39%

France 13%

Holland 5.7%

Denmark 1.2%

Liverpool, Europe's largest slave port, was responsible for 4,894 shipments, more than all French ports combined.

More than ten million men, women and children were deported from the 16th to the 19th century by Western powers, from the coasts of Africa to their colonies in America and the Indian Ocean, to be enslaved. . These powers were mainly Great Britain, France, Portugal, Spain, Holland and Denmark.

French slave ships, leaving from the ports of Nantes, Bordeaux, La Rochelle or even Le Havre, transported tens of millions of Africans from 1625 to 1848. In America, they were enslaved mainly in the colonies of Santo Domingo, present-day Haiti, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Saint Lucia, and Guyana where the natives, the Amerindians, were decimated by the French. In the Indian Ocean, they were enslaved on Ile Bourbon and Ile de France, now called Réunion and Maurice.

Slavers invented scientific and moral reasons to justify their acts. They appealed to the natural inferiority of the Negroes and relied on the Bible. They said they had to convert Africans to Christianity to save their souls. But the real reason behind the ebony trade and slavery was profit. It took a large and resistant workforce to produce cane sugar, coffee, cotton, tobacco, indigo… all the colonial foodstuffs that have permanently enriched Europe.

The slave trade & the triangular trade in the 18th century ww2.ac-poitiers.fr

Step 1:Departure from France: The ships are prepared by the shipowners (crews, sails, etc.) and leave for Africa loaded with “junk” (weapons, alcohol, fabrics, etc.). The life of sailors is very hard on board: maneuvering the sails, washing the ship, poor food, diseases like scurvy...2nd step:trafficking in Africa: Black slaves are captured from African tribes and brought by force to the forts of European slave traders on the Atlantic coast. The slaves are exchanged for “junk” (weapons, alcohol, fabrics, etc.) and embarked on slave ships heading for the Americas.Step 3:Atlantic crossing: Black slaves are crammed into the holds of slave ships in the heat and the stench. They are branded and whipped. Many fall ill and die during the crossing. They are treated like human merchandise: they have only market value.Step 4:sale and status in America: Slaves are sold at auction in America. Families are separated. They then belong to a white master who makes them work in plantations, at home or in mines. They are considered as animals: the master must feed them but can do with them what he wants.Step 5:Life of slaves on the plantations: The slaves live in small huts without comfort. They work all day in very inhumane conditions. If they disobey the master they are whipped and mistreated (chains, iron masks…). A slave who tries to run away risks death.Step 6:Return of ships to France: The white slave traders buy colonial products (sugar, coffee, tobacco, etc.) with the money from the slave trade. These goods are resold in France for the benefit of traders and shipowners: some make a fortune. Ordinary sailors are poorly paid.Revolts and end of the slave trade: Slaves sometimes revolt on ships and on plantations. In France, several intellectuals condemn slavery as a shame. The revolt of the colony of Santo Domingo in 1791 led to the independence of the island under the name of Haiti in 1804. France abolished slavery for the first time during the Revolution in 1794, but the final abolition was proclaimed in 1848.

"This is how slaves are treated. At daybreak, three lashes are the signal that calls them to work. Each goes with his pickaxe to the plantations, where they work, almost naked, under the heat of the sun. They are given for food crushed maize, boiled in water, or cassava loaves; for clothing, a piece of linen. At the slightest negligence, they are tied, by the feet and by the hands, to a ladder; the commander, armed with a post whip, gives them fifty, one hundred, and up to two hundred blows on their bare rear. Each stroke removes a portion of the skin. Then they untie the bloody wretch; they put a three-pointed iron collar around his neck, and they bring him back to work. Some are more than a month before being able to sit up. Women are punished in the same way. In the evening, back in their huts, they are made to pray to God for the prosperity of their masters. »Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, "Letter on the Blacks", Voyage to the Isle of France, 1773. (Quoted in Archeology of colonial slavery - Educational file)

The Black Code ; In March 1685, Colbert, Minister of King Louis 14, promulgated the Black Code which established the legislative framework and the legal status of the slave in French society. This text makes the slave “a being of God” and at the same time movable property.Extracts:Section 12: The children who will be born from marriages between slaves will be slaves and will belong to the masters of the female slaves, and not to those of their husband, if the husband and the wife have different masters.Rule 38: The fugitive slave who will have been on the run for a month from the day that his master will have denounced him in court, will have his ears cut off and will be marked with a fleur-de-lis on one shoulder; if he repeats another time counting from the day of the denunciation, his hock will be cut off and he will be marked with a fleur-de-lis on the other shoulder; and the third time he will be punished with death.Section 44: Declare the slaves to be movables, and as such to enter the community, to have no sequel by mortgage, to be divided between the co-heirs without preciput or birthright, nor to be subject to the customary dower, to the feudal and lineage withdrawal, to feudal and seigniorial rights, to the formalities of decrees, nor to the retrenchments of four-fifths, in the event of disposition by reason of death or testamentary.

Consequences of the slave trade on Africa: Permanent and growing insecurity.

Between the middle of the 16th century and the middle of the 19th century, the sub-Saharan population was therefore reduced by some four hundred million. Of this total, the percentage of those who were deported, from the coasts and the Sahel, is impossible to specify because of the importance of fraud and the very high number of illegal immigrants, before and after the prohibition of the slave trade. . Various sources and research lead to an increase of more than 50% in the official figures for the European slave trade (13). Evaluations of the Arab slave trade are also random. To give an order of magnitude, let's say that the figure, for the two drafts added together, must be between twenty-five and forty million. It's still highly debated, but certainly the low ratings don't take into account the enormity of the cover-ups. Nine tenths of the total losses, at least, occurred in Africa itself, which is explained by the extraordinary duration of a serious permanent and growing insecurity throughout the territory, due to the accumulation of the destructive effects, direct and indirect, of the two increasingly intensive simultaneous milkings.

A Hundred Years War that lasted three hundred years, with the weapons of the Thirty Years War, then of the following centuries. The conquest and colonial occupation, thus facilitated, have entrenched extroversion, both cultural and economic, and made the restructuring of the whole of sub-Saharan Africa and of each of its regions particularly problematic. Only about ten years ago black Africa recovered the population level it had in the 16th century, but in a very unbalanced way due to the congestion of the capitals.

The consequences of the drafts are heavy and pernicious, but many do not measure their importance.

LOUISE MARIE DIOP-MAES

Doctor of State in human geography, author of Black Africa, demography, soil and history, African Presence-Khepera, Dakar-Paris, 1996.

The slave trade had considerable consequences on the black continent, both in terms of its demography and its economic structures and development. The present bears its traces.

Slave trade, capture of blacks in Africa

Slave ship, Disposition of the blacks

Triangular trade

IN the 16th century, in most parts of sub-Saharan Africa, there were considerable cities for the time(60,000 to 140,000 or more inhabitants), large villages (1,000 to 10,000 inhabitants), often within the framework of remarkably organized kingdoms and empires, and also territories with densely dispersed settlements. This is revealed by archaeological remains and excavations as well as written sources, both external (Arab and European, prior to the middle of the 16th century) and internal (indigenous chronicles written in Arabic, the language of religion like Latin in Europe). Agriculture, livestock, hunting, fishing, a very diversified craft industry (metallurgy, textiles, ceramics, etc.), river and lake navigation, near and far trade, with specific currencies, were very developed and active. .

The intellectual and spiritual level was analogous to that of North Africa at the same time. The great 14th-century Arab traveler, Ibn Battuta, praised the security and justice found in the Mali Empire. Prior to the use of firearms, the Arab slave trade had remained marginal in relation to economic activity and population size.

From the sixteenth century, the situation worsened singularly. Thanks to firearms, the Portuguese penetrated the Congo, south of the mouth, they conquered Angola, attacked the main ports on the eastern coast and ruined them, entering what is now Mozambique. The Moroccans attack the Songhai Empire, which resists for nine years. The aggressors have firearms, while the sub-Saharans do not. Thousands of inhabitants are killed or captured and reduced to slavery. The victors seize everything: men, animals, provisions, precious objects...

Kingdoms and empires are dislocated, crumbled in principalities brought to make the war more and more often in order to have prisoners who could be exchanged, in particular against rifles, essential to be defended and to attack. This results in the displacement of populations causing new clashes, regroupings in refuge sites, the spread of a latent state of war to the heart of the continent. The raids multiplied to the point of reaching the figure of eighty per year, at the beginning of the 19th century, in the northeast of the Central African Republic, according to the Tunisian scholar Mohammed el-Tounsy, who traveled to Darfur and Ouaddaï. (current Chad) at that time (2). The percentage of captives in relation to the population as a whole therefore increased continuously between the 17th century and the end of the 19th century, and “districts that were once densely populated were reclaimed by the bush” or the forest (3).

A harmful social category

The entire socio-economic and politico-administrative fabric that had been formed was gradually perverted and then ruined. People were often reduced to self-sufficiency in defense sites that were difficult to cultivate and supply water. A huge regression in all areas. The fate of the captives worsened. A new class or malevolent social category appeared: that of brokers, caravan guards, intermediary interpreters, victuallers... the "collaborators" of the time. Certain princes tried in vain to oppose this growing trade in human beings. But the king of Portugal replied negatively to the letters of protest from the king of the Congo, Alfonso, who had nevertheless converted to Christianity. One of the latter's successors was silenced by arms. The same in Angola. The French trading post in Senegal supplied the Moors with arms so that they could attack the damel (4), who refused the passage of slave caravans. It is therefore the external solicitation that caused a great extension and the proliferation of slavery in black Africa.

Initially, the kings only delivered those condemned to death. But the Portuguese wanted large numbers, which they took themselves by attacking for no other reason. From 1575-1580, Dias Novais, first governor of Angola, sent captives at the rate of twelve thousand per year on average (5). This is twice as much, from Angola alone, as all the trans-Saharan slave trade at the same time if we refer, for example, to the figures given by the American historian Ralph Austen.

In the 17th century and especially in the 18th century, most European shipowners devoted themselves to this trade which brought in big profits, mainly the Dutch, the English and the French. In the second half of the 18th century, huge numbers were reached (read “A global approach to triangular trade”): except in the years of the Franco-English wars, hundreds and hundreds of ships embarked one hundred and fifty thousand to one hundred and four- ninety thousand captives per year according to the years (6). The growing and generalized insecurity in most regions multiplied food shortages, famines, local diseases and even more imported diseases, particularly smallpox. Endemics took hold and epidemics flourished.

Raids and internal wars

It is therefore necessary to add up all those who died during the attacks, during the transfers from the interior to the starting points and in the warehouses; suicides and rebels killed while boarding; the deaths attributable to the multiplication of raids and internal wars generated by the dislocation of political entities, by the flight of populations, by the increased desire to take prisoners; the dead of starvation (crops and reserves having been looted) and of diseases of all kinds; the deaths due to the introduction of firearms and adulterated alcohol, the regression of hygiene and acquired knowledge..., all these deaths to which must be added the captives torn from the subcontinent. We can see that this demographic deficit greatly exceeds the number of viable births, which is itself necessarily decreasing. And it would still be necessary to take into account the “shortcomings to be born”. As during the Hundred Years War, which caused France to lose half of its population, the reduction took place irregularly and differently depending on the region. It became strongly accentuated from the end of the 17th century. From the middle of the 18th century, the overall decrease was massive and rapid.

Is it possible to assess this decrease? To measure the demographic effects of the Hundred Years' War in France, we compared the number of “lighting fires” (that is to say of inhabited houses) existing before this war with the number of those counted after. Certainly, no more than in India, we have here no register of baptisms, but we know, according to the travelers and explorers of the XIXth century, that in West Africa the largest agglomerations had no more than thirty thousand to forty thousand inhabitants. They were therefore about four times less important than the largest cities of the 16th century.

From the same testimonies, one can observe that the difference was even greater for the rural population or for the number of combatants that a prince or warlord could field. Is the approximate ratio of four to one, observed in West Africa, representative of the decrease in the whole population of black Africa between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries? From Cap des Palmes (7) to the south of Angola, the losses were even higher. Gwato, the port of the Kingdom of Benin (now Nigeria), had two thousand fires when the Portuguese arrived and had only twenty to thirty left when the explorers of the 19th century appeared there (8). The American historian William G. Randles shows that the population of Angola had also been reduced in very large proportions (9). On the other hand, the regions of Chad remained fairly well populated until around 1890 (villages of three thousand inhabitants in 1878).

In present-day Sudan, depopulation began with the slave domination of the Pasha of Egypt Mehemet-Ali in 1820. In East Africa, the highlands, as in Rwanda and Burundi, remained densely populated, around one hundred inhabitants per square kilometer, contrary to what was the case in the region of Lake Malawi (ex-Lake Nyassa). In South Africa, from the first half of the 19th century, the action of the English was added to that of the Boers (10) to decimate the indigenous peoples. Overall, it seems reasonable to consider that the population of black Africa was, in the nineteenth century, three to four times less than in the sixteenth.

But can we know the size of the population of black Africa around the middle of the 19th century? The colonial conquest (artillery against guns of trade), the multiform and generalized forced work, the repression of the many revolts, the malnutrition, the various local diseases and, again, the imported diseases and the continuation of the oriental trade still reduced the remaining population by about a third, until 1930. At that time, administrative and sanitary measures began the demographic recovery which was carried out very gradually.

This evaluation was possible because, with the European presence inside the territories, certain statistical indications were added to the narrative sources (11). In 1948-1949, a general and coordinated census was carried out throughout sub-Saharan Africa. After correction for non-declaration, the population was estimated between one hundred and forty and one hundred and forty-five million people, approximately. Taking into account the increase recorded between 1930 and 1948-1949, it can be estimated that in 1930 the population amounted to between one hundred and thirty and one hundred and thirty-five million individuals, who therefore represent two thirds of the approximate population of the years 1870-1890, thus valued at around two hundred million. We conclude that the population in the sixteenth century was around six hundred million at least (ie an average of about thirty inhabitants per square kilometer) according to the results of my research. The old figures of thirty to one hundred million were totally imaginary, as shown by Daniel Noin, ex-president of the population commission of the International Geographical Union (12).

Permanent and growing insecurity

Between the middle of the 16th century and the middle of the 19th century, the sub-Saharan population was therefore reduced by some four hundred million. Of this total, the percentage of those who were deported, from the coasts and the Sahel, is impossible to specify because of the importance of fraud and the very high number of illegal immigrants, before and after the prohibition of the slave trade. . Various sources and research lead to an increase of more than 50% in the official figures for the European slave trade (13). Evaluations of the Arab slave trade are also random. To give an order of magnitude, let's say that the figure, for the two drafts added together, must be between twenty-five and forty million. It's still highly debated, but certainly the low ratings don't take into account the enormity of the cover-ups. Nine tenths of the total losses, at least, occurred in Africa itself, which is explained by the extraordinary duration of a serious permanent and growing insecurity throughout the territory, due to the accumulation of the destructive effects, direct and indirect, of the two increasingly intensive simultaneous milkings.

A Hundred Years War which lasted three hundred years, with the weapons of the Thirty Years War and then of the following centuries. The conquest and colonial occupation, thus facilitated, have entrenched extroversion, both cultural and economic, and made the restructuring of the whole of sub-Saharan Africa and of each of its regions particularly problematic. Only about ten years ago black Africa recovered the population level it had in the 16th century, but in a very unbalanced way due to the congestion of the capitals.

The consequences of the drafts are heavy and pernicious, but many do not measure their importance.

LOUISE MARIE DIOP-MAES

Doctor of State in human geography, author of Black Africa, demography, soil and history, African Presence-Khepera, Dakar-Paris, 1996.